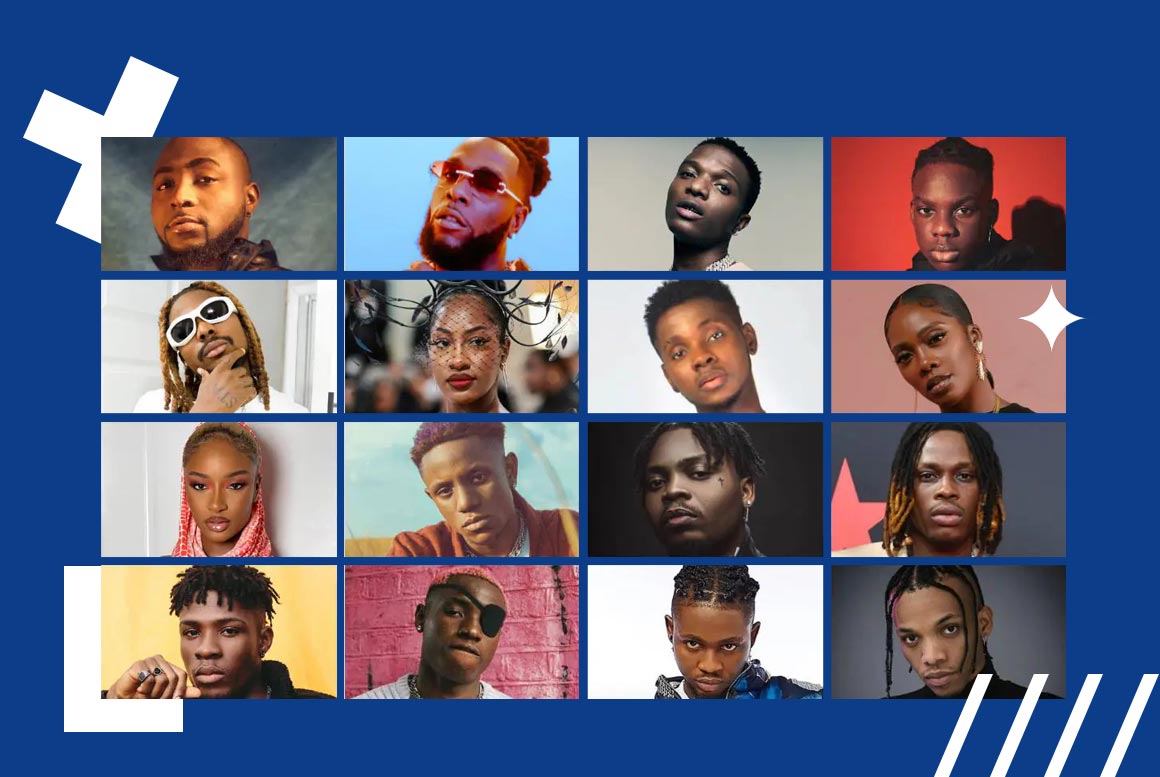

The word ‘colonizing’ will for obvious reasons always be an emotive word to those on the African Continent. But despite this (or indeed, because of this) many have been using it to show their displeasure at the dominance of Nigerian artists and Nigerian music on Afrobeats’ unstoppable march to global dominance.

Many have accused Nigerians of being ‘cliquey’ and purposely working to shut out those from the outside. Examples given are Nigerian artists choosing to promote songs/collaborators they want and not others i.e., being particularly favorable to American/Anglophone artists which will get them more radio play. Particularly loud displeasure is coming from the Francophone countries – who are saying that Nigerian artists promote songs according to who will be most favorable to their careers and close out those collaborations with Francophone artists. However, is this criticism warranted?

Many have accused Nigerians of being ‘cliquey’ and purposely working to shut out those from the outside. Examples given are Nigerian artists choosing to promote songs/collaborators they want and not others i.e., being particularly favorable to American/Anglophone artists which will get them more radio play. Particularly loud displeasure is coming from the Francophone countries – who are saying that Nigerian artists promote songs according to who will be most favorable to their careers and close out those collaborations with Francophone artists. However, is this criticism warranted?

It is undeniable that Nigerians are dominating the scene now but this is often due to years of hard work and perfecting their craft as opposed to a calculated effort (of shutting others out). The recent Netflix documentary reminded us that before Nigeria’s current dominance, Ghanaians were flying the flag for African music in the early to mid-2010s. Fuse ODG was dominating the charts with ‘Azonto’ and the song’s namesake dance was danced throughout the country in pre-pandemic times. And let’s not forget that the classics ‘Ayahede’ by Nana Boroo and ‘Swagger’ by Ruff n Smooth were staples in BBQs and christenings in church halls across the UK and the diaspora. Additionally, The GUBA Awards (Ghanaian UK Business Awards) added much-needed structure and visibility to the scene.

However, since then, Ghana has fallen off. And despite having several artists such as Black Sheriff visible on the scene – it is currently in its former glory.

What the other music landscapes on the continent lack is structure and consistency, but most importantly the ability to make incredible music that translates across the Continent and across the world. A Congolese music executive recently said that she was unhappy with the current crop of up-and-coming Congolese artists who do not have the same magic as the Kofi Olomides and Papa Wembas of the past. But she was reminded that that sound no longer resonates globally with listeners, especially with Gen Z. To replicate it would be a commercial disappointment. The best that can be done is to take inspiration from it rather than try to replicate it. Also, visa issues prevent a lot of artists from performing alongside their (Nigerian) contemporaries and therefore withholding from them, much-needed visibility and exposure on the international scene. The Francophone artists also speak of their language being a hindrance to global success.

A great example of a musical landscape that is seemingly able to rise above West African dominance is South Africa’s Amapiano. South Africa tried for a very long time to make Qom music take off. But Qom was just not resonating commercially. South Africa couldn’t blame the language barrier so instead, they went back to the drawing board and developed their sound until Amapiano was born. Now Amapiano is a force in itself with a dedicated stage at AfroNation.

It seems the answer for Nigerian dominance is for each musical landscape to mimic (as opposed to lambast) Nigeria’s – thereby creating a pipeline for new musicians, infrastructure, government assistance, and most importantly: great music.